Bridging the growing gap between utility rates and the actual cost of water will require a different approach to overcome this financial conundrum. In our previous post, we talked about the problem, and it struck a chord. As one reader commented, “If I had a nickel every time a customer came in to complain that rates are going up while they are using less and less …” Now let’s talk about solutions.

The Water Environment Research Foundation’s Pathways to One Water, a study that looks at the institutional barriers like governance, finance, regulations and culture that often keep the One Water vision from becoming a reality, includes “snapshots” of communities that have worked through these barriers, including the financial ones. We’ve highlighted a few of the programs that have created new revenue sources, won public support for higher rates or fees, and monetized environmental benefits to overcome financial barriers with integrated solutions.

“Engaging stakeholders across the community early in the planning process for One Water projects to understand their needs and concerns is critical to developing programs and projects that the community will value and support,” said Theresa Connor, research program director at WERF. “Being able to communicate the benefits to diverse audiences effectively is key.”

Thank you to WERF for giving us permission to share these success stories from the study.

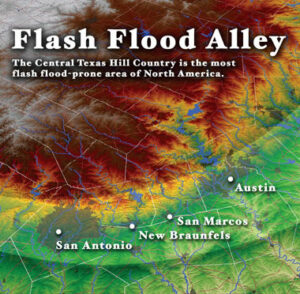

SEEK DEDICATED FUNDING: Flash flooding in Austin, Texas

Austin lies in an area dubbed “Flash Flood Alley.” The Watershed Protection Department (WPD) was formed to protect lives, property and the environment by reducing the impact of flood, erosion and water pollution. WPD works in collaboration with Austin Water, the Office of Sustainability, Austin Resource Recovery and the Planning Department. A drainage fee was created to ensure a stable revenue stream. Residential customers pay based on the number of stories in their dwellings and commercial properties based on impervious surfaces, with offsets for on-site actions.

Austin lies in an area dubbed “Flash Flood Alley.” The Watershed Protection Department (WPD) was formed to protect lives, property and the environment by reducing the impact of flood, erosion and water pollution. WPD works in collaboration with Austin Water, the Office of Sustainability, Austin Resource Recovery and the Planning Department. A drainage fee was created to ensure a stable revenue stream. Residential customers pay based on the number of stories in their dwellings and commercial properties based on impervious surfaces, with offsets for on-site actions.

LESSONS: Changing a department’s name can enhance public support and understanding, dedicated and consistent funding ensures successful programs.

LOOK FOR SYNERGIES: Resource recovery and energy generation in Oakland, Calif.

East Bay Municipal Utility District (EBMUD) was looking for ways to reduce its energy use. It had 12 digesters, but not enough organic matter. It partnered with Recology to add food waste to its digesters and received revenue from accepting this food waste. Research, funded by EPA, found that food waste was three times as powerful as sludge for producing energy. In 2012, EBMUD became the first treatment plant to be a net producer of energy – producing 120 percent of its own needs. Annual sales are about half a million dollars.

LESSONS: Establish strong public-private partnerships, seek out investors that can benefit, understand interdependencies in regulations and drivers, look beyond your own industry for synergies and opportunities.

ENSURE EQUITABLE REVENUE STREAMS: Stormwater property taxes in Santa Monica, Calif.

The city has two stormwater parcel fees that are paid annually by all property owners. These fees are assessed through property taxes and generate approximately $4 million per year. While the Stormwater User Fee is a flat fee each year, the Clean Beaches & Ocean Parcel Tax is tied to the Consumer Price Index and adjusted accordingly. Revenues from these fees support the city’s watershed management program and the city’s obligation to comply with federal and state Clean Water Act regulations.

LESSONS: Include water quality in plans to gain community support, consider available land use, open space and project life funding, wide community consultation can help gain support for taxes.

SEE THE BIGGER PICTURE: Triple bottom line accounting in Seattle, Wash.

Seattle Public Utilities (SPU) had to demonstrate to regulators how an integrated plan, which included implementing stormwater projects and delaying some combined sewer overflow projects, would significantly benefit water quality. SPU used a “Triple Bottom Line” approach to analyze, allowing them to consider financial, social and environmental benefits and costs. Dollar values were assigned to non-market social and environmental impacts. The method used MODA (multi-objective decision analysis) to allow them to clearly communicate with stakeholders the message that not only cost and water quality were considered, but also social and environmental issues.

LESSONS: Triple bottom line accounting combined with innovative modeling can result in better project prioritization and overall results.

These agencies and communities were highlighted in Pathways to One Water. Maybe you know of other programs that have helped close the gap between the cost of water and water infrastructure, and how much customers are willing to pay. Please share!